What kind of religious language is demanded from us in these days? between biblical pathos to and narrow boundaries our home and body.

Eitan Abramovich

f

Conversely, should the people fail to cry out and sound the trumpets, and instead say, “What has happened to us is just how the world works and this difficulty is merely a chance occurrence,” this is the path of cruelty…1

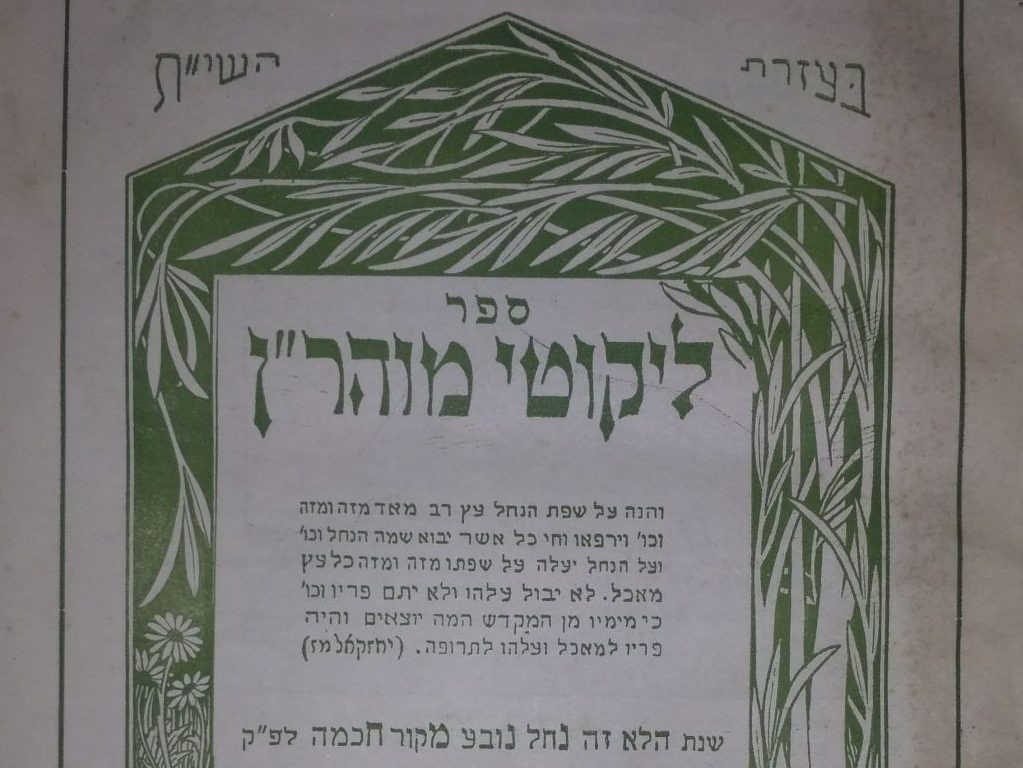

“When tragedy strikes the lives of believers, they tend to ask, ‘What does it mean?’”2 Even believers who refrain from doing so in their everyday lives–who are not attentive to the Bratslav idea of “allusions”–cannot avoid asking these sorts of questions when colossal events are going on all around them. Faced with a tragedy of biblical–or at the very least, medieval–proportions, like the 2019 Corona virus, it’s hard not to recall the way Maimonides reproached anyone who would say, “This is just how the world works.”3 Times like these demand a religious language that can give them meaning.

Responding to this demand emphasizes the unmediated connection between faith and the assumption that events in life are meaningful–whether this meaning is revealed to us or not. The function of religious language in such contexts reflects the deepest currents running within it, the unspoken foundations upon which it stands. The time of Corona demands a response, but how should we formulate it? With which language should we speak about what is happening to us?

In the same passage cited above, Maimonides speaks in the language of punishment and repentance: “This practice is one of the paths of repentance. When a difficulty arises, and the people cry out and sound the trumpets, everyone will realize that everything occurred because of their evil conduct… and this will cause the removal of this difficulty.”4 People don’t speak like that so often today, but we certainly hear the notes of biblical language when people talk about “divine wrath,” about “judgement against all the nations,” and about what God wants from us in the present situation.5

Personally, these biblical notes are cause for distress, and remind me of how Rav Shagar said that the religious world is caught up in supernal worlds “which people will never be able to fully comprehend, and which therefore inspire doubt in a person who focuses on them.”6 My distress comes from the attempt to use the unquestionable scale of events in order to transcend beyond the human, to use words to conquer events that are greater than us. It is as if the very ability to restore “divine wrath” to our lexicon grants us an anchor amidst all the chaos, framing it in a familiar context.

I want to use Rav Shagar’s discussion of the meaning of providence in order to suggest a different direction we might take.7 Great events are shaking the world, but perhaps the role of religious language is not to position God behind the events. Perhaps religious language is not about grabbing onto faith in someone greater than the events, but rather it should open us up to what is happening in the narrow contexts into which our lives have shrunk. Rav Shagar writes: “God is not just someone who presides over events from the outside… rather he is the vitality within the events.”8 His discussion of providence focuses on what events mean to us. Taking this as our starting point, perhaps the vitality of these days must be found not in the standards of a meta-narrative, but in the way we experience them. We must find the hidden depth within events in a movement from the bottom upward, as Rav Shagar writes in a different context.9

I seek a religious language that will not simply echo the artificial drama of news broadcasts, but which will touch on the outcomes of the forced isolation in our homes, and the disruption of our daily lives. It will speak to the experience of the body threatened from every direction. It will give us words for our self-distancing from society and our gathering inward with close family. “The meaning of history is found within it, just as the person is found within it.”10 Despite how good it feels to speak biblically, perhaps in these times too we must speak only from the place where we really stand.

Translated by Levi Morrow